“Was it a government action, or did they do it themselves because of pressure?”

This is inevitably among our first questions when news breaks that any expressive work (a book, film, news story, blog post etc.) has been censored or suppressed by the company or group trusted with it (a publisher, a film studio, a newspaper, an awards organization etc.)

This is not a direct analysis of the current 2023 Chengdu Hugo Awards controversy. But since I am a scholar in the middle of writing a book about patterns in the history of how censorship operates, I want to put at the service of those thinking about the situation this zoomed-out portrait of a few important features of how censorship tends to work, drawn from my examination of examples from dozens of countries and over many centuries. The conclusions here are helpful for understanding this situation, but equally applicable to thinking about when school libraries bow to book ban pressures, how controversies impact book publishing in the USA and around the world, and historical cases: from the Inquisition, to censorious union-busting in 1950s New Zealand, to the US Comics Code Authority, to universities censoring student newspapers, etc.

The first and most important principle is that we cannot and should not draw a line between state censorship and private or civilian censorship. Many analyses of censorship start by drawing this line and analyzing state action and private action separately. There are many problems with trying to draw such a line, but the most important is this:

The majority of censorship is self-censorship, but the majority of self-censorship is intentionally cultivated by an outside power.

In other words, when we look at history’s major censorious regimes, all of them—I want to stress that; all of them—invested enormous resources in programs designed to encourage self-censorship, more resources than they invested in using state action to actively destroy or censor information. This makes sense when we realize that (A) preventing someone from writing/saying/releasing something in the first place is the only way to 100% wipe out its presence, and (B) encouraging self-censorship is, dollar for dollar and man-hour for man-hour, much cheaper and more impactful than anything else a censorious regime can do.

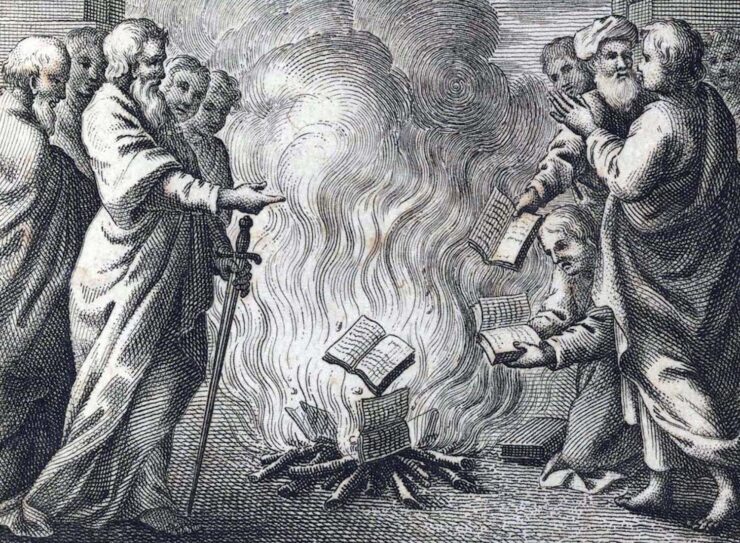

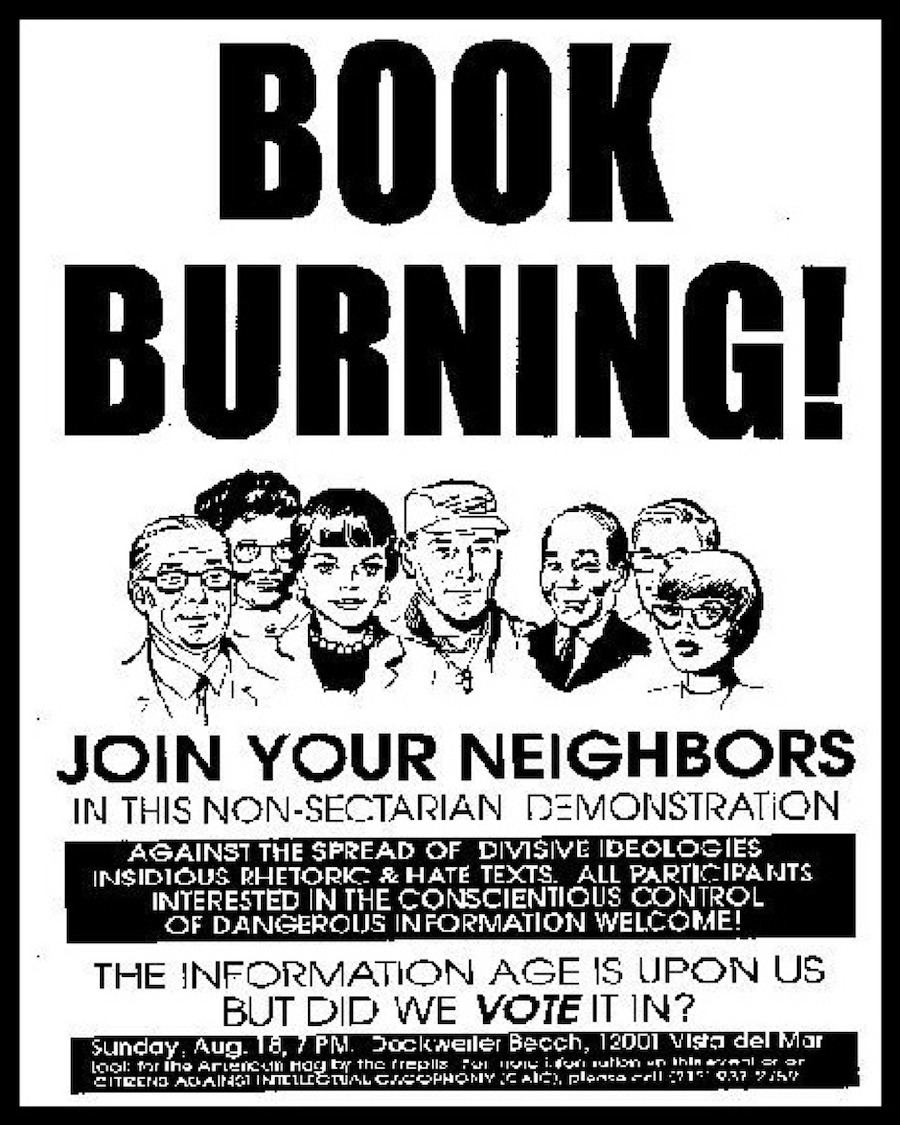

Think about how many man-hours it takes to search thousands of homes one-by-one to confiscate and destroy a particular book, versus how cheap and easy it is to have a showy book burning or well-publicized arrest of an author which scares thousands of families into destroying the book if they have it. Will the show trial or book burning scare people into destroying every copy? No, a few will keep it, even treasure it more because of its precious scarcity, but the number who do is no larger than the number whose copies would’ve been missed by the ever-imperfect process of the search, and the cost in manpower is 1/1000th of the cost of the search, freeing up resources for other action.

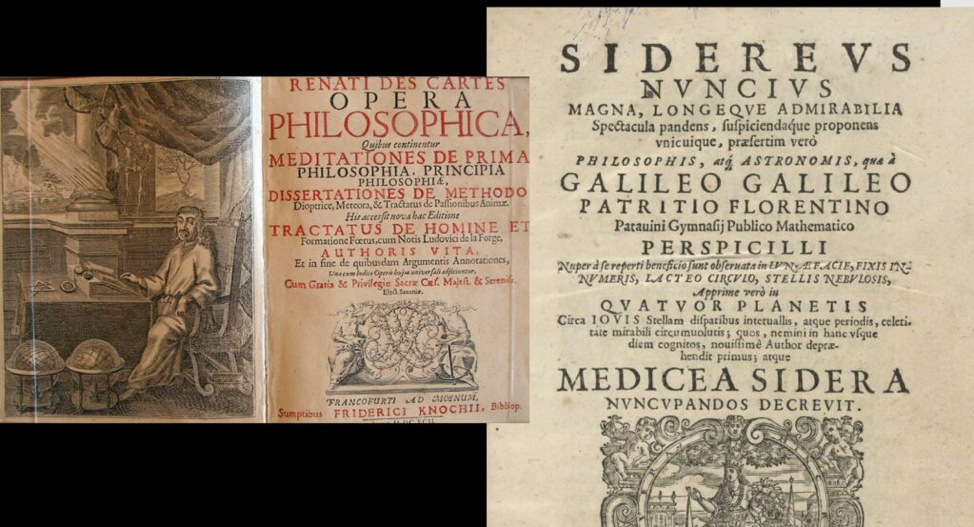

A great question to get at this is: Did the trial of Galileo succeed or fail?

If we believe that the purpose of the Inquisition trying Galileo was to silence Galileo, it absolutely failed, it made him much, much more famous, and they knew it would. If you want to silence Galileo in 1600 you don’t need a trial, you just hire an assassin and you kill him; this is Renaissance Italy, the Church does this all the time. The purpose of the Galileo trial was to scare Descartes into retracting his then-about-to-be-published synthesis, which—on hearing about the trial—he took back from the publisher and revised to be much more orthodox. Descartes and thousands of other major thinkers of the time wrote differently, spoke differently, chose different projects, and passed different ideas on to the next century because they self-censored after the Galileo trial—an event whose burden in money and manpower for the Inquisition was minute compared to how hard it would have been for them to get at all those scientists. The final form of Descartes’ published synthesis was self-censorship—self-censorship very deliberately cultivated by an outside power.

The structures that cultivate self-censorship also cause what we might call middleman censorship, when one actor (organization or person) is pressured into censoring someone else’s work, but via the same structures (fear, self-preservation) that cause self-censorship. The publisher who pulls a controversial title, the screenwriter who removes some F-bombs or queer content from a colleague’s first-draft script, the arts organization which refuses to screen a politically provocative film, or the school librarian who makes use of Scholastic’s infamous option to “opt out of diverse books” at a school book fair, these people are not censoring their own creations, but their complicity in censorship is often motivated by the same structures of fear and power which censorship regimes use to cultivate self-censorship. Outsourcing censorship to the populace—to the editor, the cinema owner, the awards committee, the teacher, or the author—multiplies the manpower of a censorship system by the number of individuals within its power, making it the single most effective tool of such systems. Since self-censorship and middleman censorship are cultivated by these same deliberate systems of fear, they must be analyzed together, even as we still recognize the great difference between censoring a friend’s book and censoring one’s own.

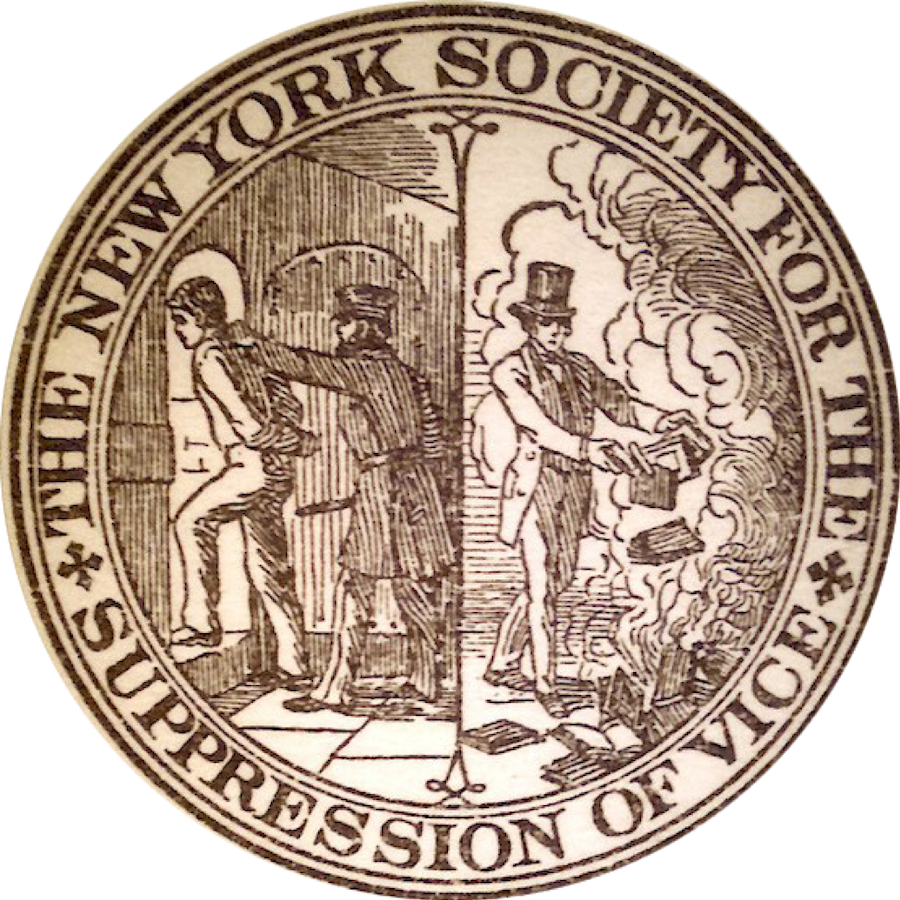

Let’s look at another example closer to the present than the Inquisition: comic book censorship in the 20th century. As many of you are aware, in 1954 a moral panic came to a peak across the English-speaking world (USA, UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, etc.), blaming violence and sensuality in comic books for an epidemic of so-called juvenile delinquency. New Zealand (which has state censorship) created a state office for comics censorship, while in the USA (whose First Amendment prohibits Congress from taking such action) politicians, who knew they could capitalize on this moral panic, exerted pressure on comics companies until they created the supposedly-voluntary Comics Code Authority to censor comics. Grocery stores and most comics shops then stopped shelving comics that didn’t undergo its censorship, bankrupting publishers and hurting authors and artists. Now, fast forward to the ’60s and ’70s, when the US Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum and again Congress could take no direct action against it, but publishers of comics centering Black heroes such as Black Panther (first introduced in Fantastic Four #52, in July 1966) suddenly found that the Comics Code Authority censorship process was being much more picky about their Black characters than their White characters, declaring things even as mild as a drop of sweat on the forehead of a Black astronaut as “too graphic” since it “could be mistaken for blood.” This resulted in grueling extra work and perennial delays for such titles, pressuring comics companies to depict fewer Black heroes.

If we ask “Did the US government censor Black Panther?” our answer would be no if we insist on separating state action from self-censorship, since in this case the result is three levels of action removed: Congress put pressure, that created the Comics Code Authority, its individual censors felt anxious about race (egged on by government amplification of racial tension), those censors pressured comics publishers, comics publishers pulled titles and comics artists included fewer Black characters. Even while faithful to “Congress shall make no law…” state action was able to create a middleman censorship cascade in which no direct government agent or employee acted, but which the state caused and intended to cause. Did the FBI operations that were trying to undermine Civil Rights activism send agents to pressure the Comics Code Authority? We don’t need to know whether they did or not to say confidently that the censorship of Black Panther and titles like it was a deliberate and intended consequence of state action. The same is true whenever and wherever state action causes private individuals and organizations to self-censor out of fear and pressure.

When we hear self-censorship discussed in the media, these days it is most often brought up when discussing cultural pressures or other non-state action, such as in the depressingly familiar rhetoric claiming that trends like political correctness, “cancel culture,” etc. are censorious. We are all aware of how this rhetoric is often used in bad faith to attack rather than defend free expression (on college campuses, for example), but there is a second and separate way it is destructive: this rhetoric advances the illusion that self-censorship and middleman censorship are primarily civilian phenomena caused by public attitudes and individual or community actors, making it easier to disguise how often they are, in fact, a direct and intentional result of government or other large-scale organized action. And because they work through projection of fear and power, they can also affect people living in regions or nations outside the direct power of the government doing the censoring, resulting in citizens of other nations having their thoughts and actions shaped by the tactics which outsource censorship from state actors to anyone who sees them and fears them.

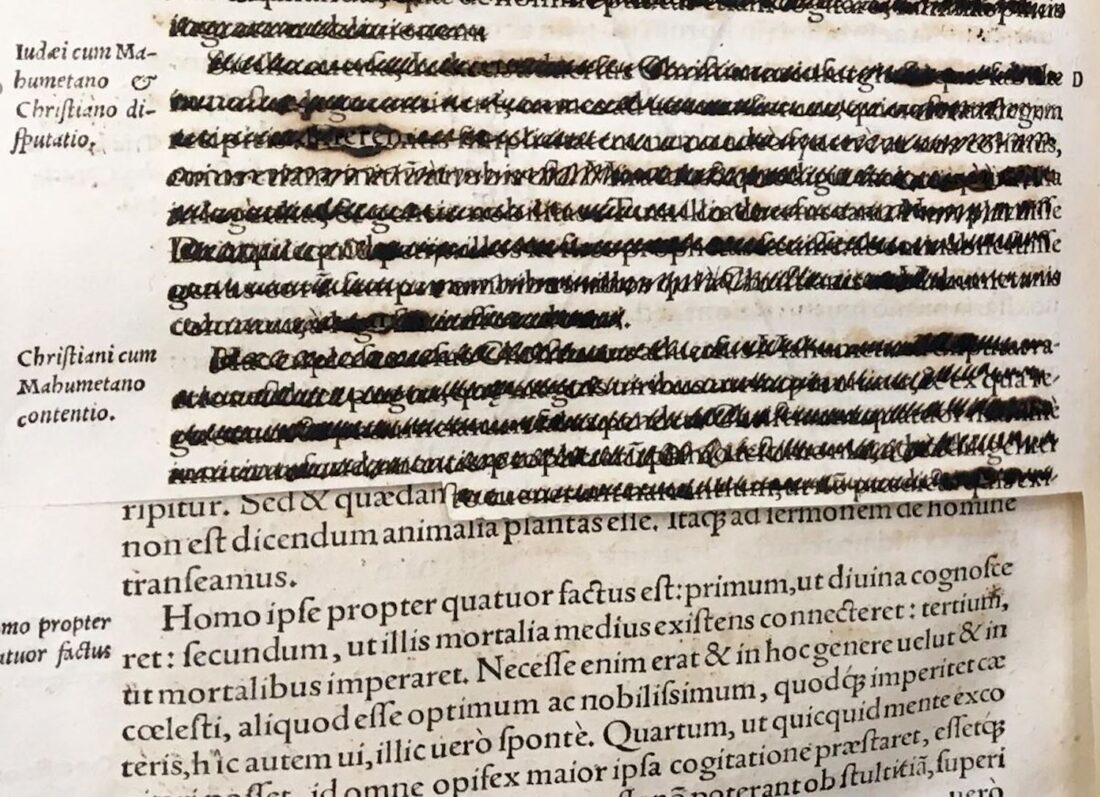

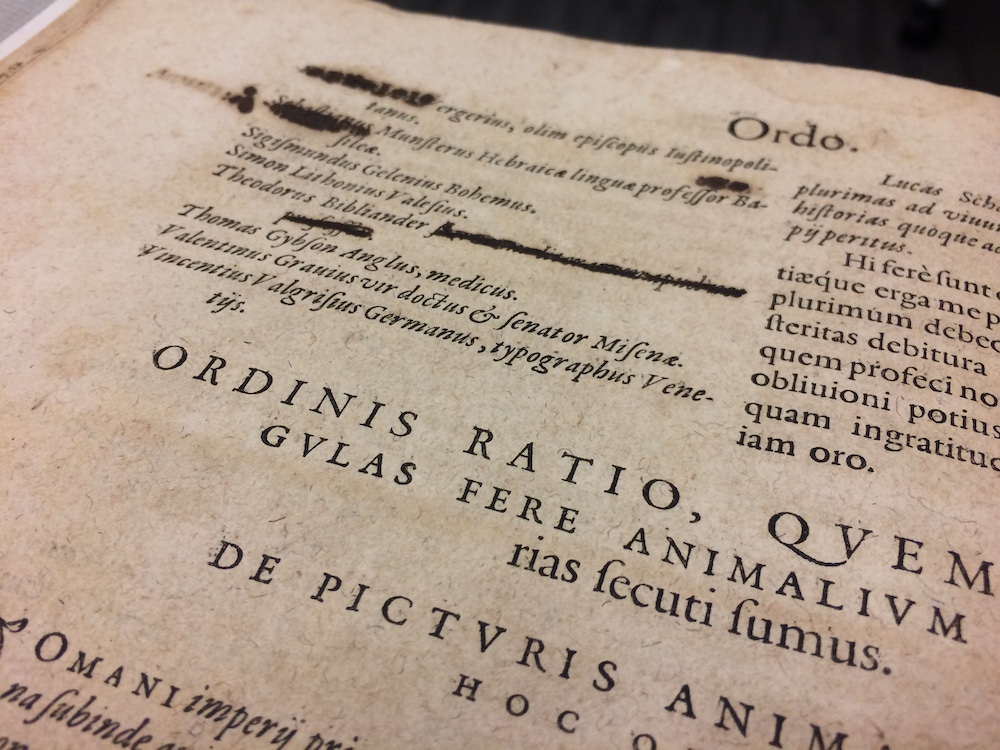

I don’t want to dwell too much on what our evidence is that state-censorship often aims to operate through self-censorship or middleman censorship (the book I’m currently writing, Why We Censor: from the Inquisition to the Internet, will have many examples from different times and places of the motives which enable censorship and, especially, how institutions make use of self-censorship) but to give one more very vivid one, here is a photo of some pages from a treatise on scientific logic by Cardano, published in the 1500s. Cardano was condemned by the Inquisition, and the order was given to expurgate copies of the text, meaning going through based on a guide published in the Inquisition’s Index of prohibited books.

In the copy shown above (now at my university’s library in Chicago), an Inquisitor has faithfully gone through page by page and excised the controversial sections, scribbling them over with ink, or when both sides of a page were condemned cutting them out with scissors. This took hours of work by a highly-trained, expensive-to-hire, Latin-reading Inquisitor. It would have taken seconds to throw this book on the fire.

The Roman Inquisition in the 1500s was constantly complaining about its desperate lack of personnel (not enough Inquisitors, not enough censors to read books, not enough police) as it tried to keep up with the exponentially-growing flood of books enabled by the newfangled printing press. Why would such an organization waste hundreds of man-hours per copy on crossing out pages when they could have trivially burned the book and moved on?

Let’s look at another example:

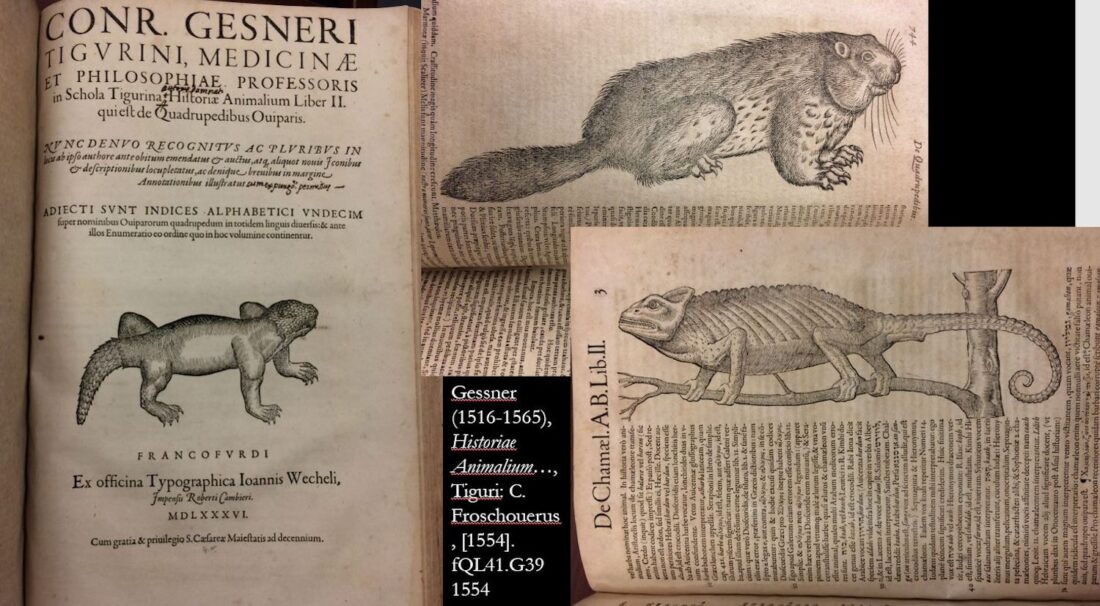

This example is from an encyclopedia of animals by Konrad Gesner from the late 1500s, an entirely secular book with zero controversial content. But Gesner was a good scholar, and cited his sources, always placing near his picture of each animal a note saying “many thanks to the learned and excellent Dr. So-and-so of Such-a-place for sending me this picture.” The Inquisition’s order for this book was that Catholics were allowed to own the book, and all the content in it, but wherever Gesner thanks a scholar, if the person he thanks is Protestant, the Inquisitor or the book’s owner must cross out the words “learned and excellent” to enforce the Church’s lesson that Protestants were not learned and excellent, they were bad and wrong.

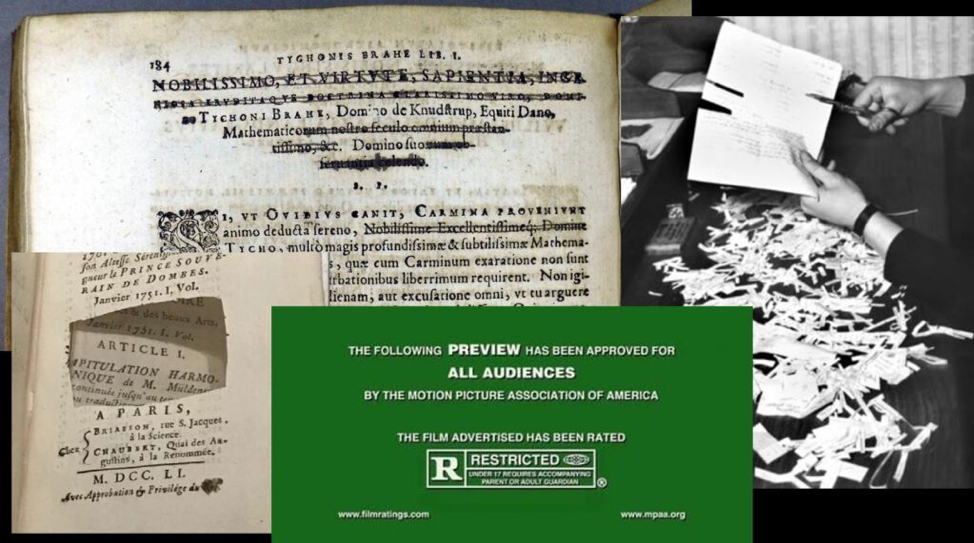

This use of (limited!) manpower is absurd to the point of hilarity if we imagine the Inquisition’s goal was the destruction of information, but it wasn’t. It was like Bart Simpson repeating a phrase on the blackboard, the rote expurgation turned this completely secular book into a tool for projecting the Inquisition’s power, as you turned the pages, and page after page saw that stark black patch of crossed-out text, reminding you over and over of the presence and power of the Inquisition. It was a projection of power, something to make authors and printers think “I don’t want my book to go through that.” This also made use of middleman censorship: one could apply to the Inquisition for an official license granting permission to own restricted books, but one of the conditions of this seeming-privilege was that you yourself had to go through and cross out the sentences they banned. This made the very people who loved and wanted to read restricted books into middleman censors excising text from their own copies, and experiencing the same mortifying and emotionally manipulative reinforcement a child does when forced to write a motto on a blackboard. It was a didactic tool designed to be a constant reminder of the authority’s presence—just like the Comics Code Authority seal on the front of a comic, or the movie ratings green title card on a film.

Now, in the case of very large-scale censorship regimes, like the Inquisition, Stalin’s USSR, and indeed modern China, it is hard to believe they actually do suffer from limited resources. The image rises in our minds of Orwell’s imaginary Ministry of Truth, which has infinite resources, infinite manpower, and whose Thought Police partner the Ministry of Love can surveille every citizen every instant of the day. No real censorship regime has ever approached that. When we look at internal documents from the USSR, the Inquisition, all of them, we see constant complaints about lack of information, lack of people, lack of funds—they always depict themselves as in emergency crisis mode, desperately trying to keep up with an overwhelming task. In the period that Spain’s Inquisition was wildly out of Rome’s control, the Roman Inquisition even printed manuals to guide its Inquisitors on how to bluff their way through pretending they were on top of what Spain was doing! Even though they did have huge resources, those resource still were and are nowhere near enough to actively police all people and all things at all times.

But that sense of desperation and lack of manpower is only visible in the internal presentation of such regimes, carefully concealed from public view. It is in the external propaganda of such regimes that they present themselves as always on top of things, always everywhere, always watching, always as stable and effective as Nineteen Eighty-Four’s ministries. At the same moment that Rome was publishing guides for Inquisitors to BS their way through the activities of rival inquisitions, Rome was also publicly proclaiming that it had everything under control. This illusion of infinite resources itself is one of the goals of such regimes, making people more afraid, and less willing to defy. It is about projecting power, and we must not fall for it as we evaluate the actions of such regimes asking “Why did they do A not B?” If we believe they have infinite resources, we will always imagine some strategic mastermind plan behind it, and fear that, if we don’t see the reason, there must be something big and scary underway that we don’t know about. This coercive fear is especially effective at extending censorship beyond a power’s borders to citizens of neighboring regimes, who are not themselves under the censor’s power but can still feel that they or their friends are vulnerable to a vast, imagined Orwellian power. If we remember that Nineteen Eighty-Four is fiction, its infinite resources impossible, that these organizations all need to conserve resources, many more of their tactics become transparent.

Fear is one of the two main ways powers cultivate self-censorship and middleman censorship, but its partner is projection of power, which is not quite the same.

When we go to a movie theater and see the big green screen with “This Film Has Been Rated G, etc.” we aren’t intended to feel active fear of the movie ratings board, but we are intended to feel its power, its presence, its reach. In addition to telling us the film’s rating, that green screen is a daily reminder of the power of that censoring body, just as much as a government poster on a wall. Seeing that ratings reminder on every film we ever see growing up subtly shapes the thought of every person who enters the filmmaking industry—or even aspires to—and every movie script in which profanity, violence, or sexuality appears is shaped, at least a little bit, by the writer’s consciousness that the work will be judged on those criteria, and that moral attitudes toward them could shape the film’s, and the writer’s, financial future. Even if the writer goes ahead and keeps those F-bombs, the period of thinking about the issue, the debates with collaborators about the issue, those thoughts and conversations constantly reaffirm to the very people having them the presence and power of the censoring body, shaping thought, and art.

For this reason, censorship systems want to be visible. They don’t tend to invisibly and perniciously hide their traces, they tend to advertise it: in big printed letters, blacked-out passages, or a brightly-colored screen. Even when a blocked website redirects you to ERROR: THIS WEBSITE IS BLOCKED, that is a deliberate choice—very different from, for example, the period in which Amazon’s website invisibly redirected searches away from Hachette titles to non-Hachette books. The Inquisition, USSR, movie ratings board, Comics Code Authority, all such regimes could have done their work invisibly too, but instead they tend to prefer to advertise their presence, because that causes the most self-censorship ripple impact. (Amazon’s goal was not to be feared and seen as a censor, but to hurt Hachette financially, hence its very atypical tactics.)

The many nations in the world which censor their internet design a variety of experiences for the user who attempts to go to a blocked website. Some redirect to a screen which explicitly states the page is blocked by the government and why, others to a generic error page, others load a blank page or simply leave the page loading forever. As a rule they do not (as Amazon did) seamlessly load a different page. While the blank or ever-loading page may seem like it is trying to make the censorship invisible, such regimes make certain their populations know that the web is censored and what those endless loading times really mean; in fact, in such a system, any time any webpage loads slowly, the user experiences a spike of anxiety wondering if this is censorship, and if trying to go to a few too many forbidden pages might lead to a knock at the door. Just as a black line through “learned and excellent” could turn an encyclopedia of animals into a tool for projecting power, when a page loading slowly is the sign of censorship, that turns every internet glitch into an emotional reinforcement of state power, saturating lived experience.

Censorship regimes use their visibility to change the way people act and think. They seek out actions that can cause the maximum number of people to notice and feel their presence, with a minimum of expense and manpower. This is why deliberate unpredictability is a common tactic of censorship regimes, not trying to target every person/work/organization who does a particular thing (purchases pornography, possesses banned Jazz, once belonged to a now-suppressed political organization, tries to load blocked websites, and so on). Rather they target a few people unpredictably and conspicuously, so that everyone else in a similar situation will feel fear, and self-censor or middleman-censor more, including self-censoring in arenas unrelated to what was targeted (i.e. someone who both owns porn and supports a political resistance party might become more afraid to support that party after a widely-publicized crackdown on someone who owned porn, or vice versa). This is an extremely potent and cost-effective tactic, and a go-to for many regimes, from Imperial Rome, to enforcement of anti-sedition laws in WWI and WWII, to today’s anime/manga censorship, etc.

When using deliberate unpredictability, regimes look for potential targets who themselves lack substantial political and economic power, but where a crackdown would be widely publicized and discussed, instilling fear in a large group of people who consider themselves similar to the object of the crackdown. And such regimes look for targets connected to existing networks of information dissemination, so word of the crackdown will spread easily (a famous person like Galileo, a well-connected person like a newspaper editor or blogger, an organization with newsletters and its own information networks, etc.). This makes every organization under such a regime which does fit that profile (visible to a substantial network but not powerful in itself) extra cautious, and more likely to self-censor or middleman-censor. This tactic is especially effective at frightening people outside a censor’s direct power into fearing possible consequences to friends, organizations, or themselves, psychological manipulation which allows regimes to coerce other nations’ citizens into becoming part of their outsourcing of censorship. Anyone can become complicit. Just as the price of freedom is eternal vigilance, one price of free speech is eternal humility, recognizing that none of us is immune to becoming a tool of censorship if we fail to recognize how its manipulative tactics shape and distort our thoughts and actions.

As I said, I have a whole book’s worth of work on patterns in how censorship regimes work, and wanted to keep this short, and focused on principles which help us think about these questions. For more details and examples, you can see my recent lecture on the topic. But for this particular reflection, please remember these five points:

- The majority of censorship is self-censorship or middleman-censorship, but the majority of that is deliberately cultivated by an outside power.

- For this reason, we cannot consider state and non-state censorship separate things. State censorship systems work dominantly via shaping and causing private censorship.

- No real censoring body has ever had the resources of Orwell’s fictitious Ministries—not even the Inquisition or the great totalitarian powers of modernity like the USSR, but they want us to think they do. Real censorship regimes tend to see themselves as constantly underfunded and understaffed, racing to grapple overwhelming crises, while attempting to seem all-reaching and all-knowing as a part of their own propaganda. We must analyze their actions remembering that the need to conserve resources and seem stronger than they are shapes everything they do.

- Censorship aims to be visible, talked about, seen, feared. This increases its power.

- Censors’ projection of fear and power is a form of deliberate psychological manipulation which can outsource censorship far beyond the censor’s sphere of control, even to citizens of other nations. We can only combat it if we work hard to cut through the Orwellian illusion and remember the realities of how censorship works.

While we must discuss and analyze censorship when we see it, we must also remember that censorship wants to be discussed and thought about, and then think about how we can make sure our responses don’t strengthen the very thing they seek to oppose, by increasing the fear felt by those within the power of such regimes. The blacked-out word on the page and the website that loads frighteningly slowly create spikes of fear in those who see them, fear which advances the goals of the censorious regime. So can the email inviting a comment which makes an author/editor/commentator/fan fear the consequences.

“The only weapon worthy of humanity, of tomorrow’s humanity, is the word.”

So wrote Yevgeny Zamyatin (1884-1937), one of the fathers of dystopia, author of We, a lover and writer of science fiction, who passionately supported the Russian revolution in its hopeful early days, and later opposed Stalin just as passionately. Subjected many times to imprisonment, violence, and smear campaigns, and ultimately forced to flee his homeland (sacrificing en-route the only manuscript his now-lost favorite work Attila), Zamyatin understood how complex is our great and worthy weapon, the word—how it can serve the foes of hope as well as its friends, and must always be wielded thoughtfully. I leave you with some passages from his letters and essays1, to remind us that we face these crises in solidarity with many allies across time’s diaspora.

The author of the present letter, condemned to the highest penalty, appeals to you with a request to change this penalty to another. My name is probably known to you. To me as a writer, being deprived of the opportunity to write is nothing less than a death sentence. Yet the situation that has come about is such that I cannot continue my work, because no creative activity is possible in an atmosphere of systematic persecution that increases in intensity from year to year

—From “Letter to Stalin,” Yevgeny Zamyatin, written 1931

Today is doomed to die—because yesterday died, and because tomorrow will be born. Such is the wise and cruel law. Cruel, because it condemns to eternal dissatisfaction those who already today see the distant peaks of tomorrow; wise, because eternal dissatisfaction is the only pledge of eternal movement forward, eternal creation. He who has found his ideal today is, like Lot’s wife, already turned into a pillar of salt, has already sunk into the earth and does not move ahead. The world is kept alive only by heretics: the heretic Christ, the heretic Copernicus, the heretic Tolstoy. Our symbol of faith is heresy: tomorrow is inevitably heresy to today, which has turned into a pillar of salt, and to yesterday, which has scattered to dust. Today denies yesterday, but is a denial of denial tomorrow. This is the constant dialectic path which, in a grandiose parabola, sweeps the world into infinity. Yesterday, the thesis; today, the antithesis; and tomorrow, the synthesis.

Yesterday there was a tsar, and there were slaves; today there is no tsar, but the slaves remain; tomorrow there will be only tsars…

The only weapon worthy of humanity—of tomorrow’s humanity—is the word. With the word, the Russian intelligentsia, Russian literature, have fought for decades for the great human tomorrow. And today it is time to raise this weapon once again.

—From the essay “Tomorrow,” by Yevgeni Zamyatin, written 1919-20

An earlier version of this essay appeared on the author’s blog, ExUrbe.com

- Translations by Mirra Ginsburg, editor of A Soviet Heretic, the English language collection of Zamyatin’s essays, which I cannot recommend enough! ↩︎